Ways that are Dark

2018-09-10

I have been reading, recently, a book about China called "Ways that are Dark" by Robert Townsend, which was published in 1933 and subsequently banned in China and denounced by sinologists as "racist." It may not be precisely racist, but it certainly is an indictment against the Chinese ethnos and social mores. I wouldn't suggest that a Chinese person read it even if it has been translated into Chinese.So why would I deign to read it? I'm someone who likes the Chinese immensely: enough, in fact, to marry one. My daughter is half-Chinese. I shouldn't like to hear, necessarily, a long screed against folks who've become family. And yet, I am curious to know what life was like according to a career American diplomat in China in the 1930s, which Townsend was. In particular, he doesn't shy from talking about the poverty of that time. Seeing through his eyes the abjection of the Chinese at that time--a time of social turmoil--gives us baseline to gauge how far the Chinese have come since.

Some vignettes:

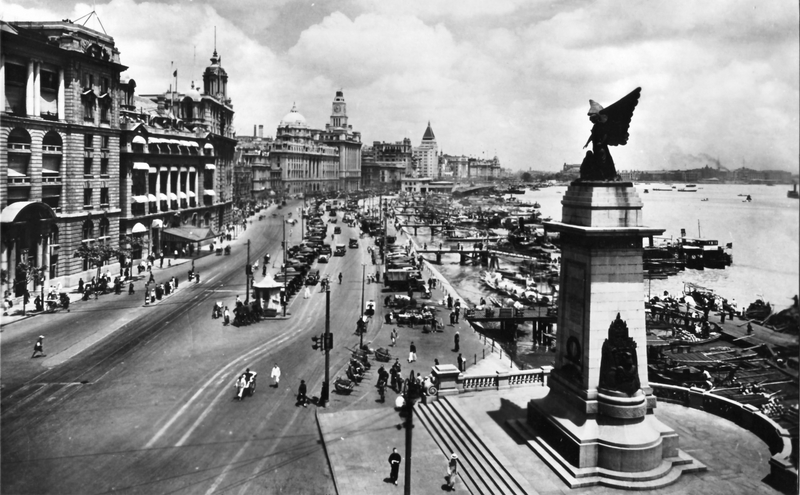

1. Townsend starts out in Shanghai, near the Bund, where looking out over the waters he sees poor, filthy families in their sampans gathering around passenger ships like remoras. There they lift bamboo poles with nets fitted to the ends up to the drainage holes of the ships. When the ships cast off their refuse--banana and orange peels, day-old bread crusts, plate scrapings--they catch them in the nets and bring them down to their boats where the children fall on them ravenously.

2. Townsend also notes that for much of China at the time, rice was something of a luxury. Although it was grown widely, it was mostly used for sale, and no more than 20% of one's own meal was ever given over to it. The rest was typically made up of sweet potato or corn. This accords pretty well with my mother-in-law's memory of her own childhood. One ate a litte rice and mainly potato; on your birthday, you'd get a whole bowl of rice, maybe.

3. At the time, rickshas were still a primary means of transportation and 'coolies' carried cargo on their backs. Townsend marvels at how the Chinese are able to work all day while being so lean. He notes that whereas a Westerner works on stored fat, the Chinese seem to have none, and so rely on a habit of constantly eating. Townsend notes that every time a Chinese worker at the time got a little money, he would immediately go and spend a portion of it on bread. In this way--by eating throughout the day--he was able to continue working much longer than an Englishman or American would have been able to. This habit of eating constantly, said Townsend, carried over to the upper class as well, who could be seen spending a surprising amount of time in restaurants.

I have taken just a few things out of the book, which is otherwise a very negative look at the Chinese. In page after page, Townsend harangues about what he considers dissembling and poor social institutions as reasons for China's immiseration. Time would prove Townsend almost entirely wrong, of course, at least insofar as his suppostition that the Chinese would remain hopelessly disordered. In fact, strict and ancient social controls have been a key to Chinese cohesion, but Townsend was not in a position to see how it could be so. Chinese society is more of a clan structure, meaning inter-family trust is high; Western society is more individualistic and therefore institutional trust must be higher.

At the moment, Western society is coming apart and Chinese society (and Asian society in general) has been remarkably robust in the face of those effects of modernity which lead to decadence. I'll be interested to see a Chinese travelogue through North America in a hundred years, parts of which I expect will be quite nice after a breakup and reformulation into smaller, more defined ethnic units.

At the moment, Western society is coming apart and Chinese society (and Asian society in general) has been remarkably robust in the face of those effects of modernity which lead to decadence. I'll be interested to see a Chinese travelogue through North America in a hundred years, parts of which I expect will be quite nice after a breakup and reformulation into smaller, more defined ethnic units.

Feel free to follow my wechat English course and blog, Josh老师.

no comment

Comment